Steel is Real, they say. We listen, sort of, because we’ve all been told this was the case by Luddites who eschew carbon bikes and still use a flip phone. It’s also safe to say that many of us MAMILlian types have gone down the pathway to the light (and brittle) side of cycling. When I started my custom titanium frame company in the early 2000’s, it was the beginning of the Carbon Explosion, when anyone with any opinion about cycling was looking at the marvel of bikes made of fibers. And, dear reader, there were plenty of opinions. Most of them resulted in people buying plastic bikes instead of the ones I was designing. It was the dawn of the Fred Era.

Those early carbon bikes were amazingly light, seeming to defy gravity when compared to metal frames. Sure, aluminum and scandium frames were light, but had bone-jarring rides. Carbon, on the other hand, was even lighter, could be made stiffer, and could have funny shapes. Each year brought out a lighter, stiffer, more aero frame design, and like many of my peers, I fell for the siren song of resin and woven fabric. My titanium dreams had faded, and my company folded, so I bought a 2008 Orbea Orca frameset, in glittery blue and black, and built up a gorgeous, freakishly lightweight bike. My titanium souvenirs from a failed project hung on the wall, glaring balefully at their plastic nestmate.

The Orca was a beautiful bike, with sweeping lines, sculpted curves, and a gorgeous, flowing form. It was a designer’s bike, not an engineer’s, and it showed the beauty that a molded bicycle could have. It was fast and agile, descending like a fighter jet: agile, quick, precise, and frighteningly fast. I regularly exceeded 55mph on it, which is really, really stupid.

That stiff, precise frame, with large diameter seatpost, and state-of-the-art 21c tires at high pressure (110psi) taught me how to judge the aggregate size in any pavement or chip-and-seal purely by the frequency that the surface hammered the bike into my ass and palms. I felt every pebble in every surface and took inventory of all of my dental fillings after every ride. In 2011, I sold that beautiful bike, and honestly, don’t miss it at all.

I went back to my first titanium design, a frame I had dreamed up while my primary bike was a 2000 Bianchi Axis. I liked the Axis; it was an aluminum ‘cross frame, with clearance for 35c tires, and I enjoyed playing with it on singletrack and gravel roads. For an entire summer, it supplanted my mountain bike, and I hammered it on Colorado trails, chasing my 26er-wheeled mountain bike buddies. It was a blast, and the aluminum frame and fork stiffness wasn’t a problem- it was a feature.

However, while riding it on a park service chip-and-seal road, I fantasized about the legendary forgiving ride offered by titanium. As a designer, I pass miles on my bike by thinking about what I want the bike to really do, what components would be better, and how I can get my ideas to fruition. As it turned out, the only way was to study frame design, consult with knowledgeable people, and find someone to weld my frames. It took some effort, and a significant amount of money, but it was fun.

My friends told me that a road bike with slightly relaxed angles, tall head tube, clearance for big ‘cross tires, and disc brakes was stupid, and that no one would ever be interested in a bike like that.

Clearly, Nostradomus is not threatened by anyone in my riding group.

After selling the Orca and revisiting my original design, I realized how much I liked the feel of the metal bike. Titanium and steel have similar, yet distinctly different, ride qualities. To me, titanium feels dampened, smooth, and flowing, able to handle multiple surfaces with aplomb, and without transmitting high-frequency vibrations to me. As a life-long skier, I see it as an equivalent to a wood-core race GS ski. The dream metal, it cries out to your bank account, seeking to reduce your balance while simultaneously adding value to your life.

Conversely, my perception of steel was not positive. I’d had steel in the past, from my early ’70’s Schwinn Stingray (with training wheels) to my late ’70’s Takara 10-speed (with foam bar wrap and stem-mounted shifters) and my mountain bikes, but I’d never really ridden them on the road. A late-night eBay find brought a faded ’98 Ibis Spanky frame to me. My perception of steel changed in a heartbeat.

The Spanky, once re-painted and decaled, and rebuilt with modern components showed me what steel could be: crisper, a bit livelier than titanium, with a discernible pushback for every pedal stroke. It’s my race slalom: snappy, quick, and tactile. The Spanky seems to float, hardly touching the road surface. It accelerates smoothly like a luxury car, erases road imperfections, and descends like a hellion. The old frame design allows a pair of 25c tubeless tires and not much more, and the 1″ steerer tube flexes a bit, but the feel of the bike is just delicious. The butted MoreOn tubing delivers a smooth but lively ride, and the bike is phenomenally comfortable on pavement, chip-and-seal, roadbase, and more. Although Ibis has a well-deserved reputation as pioneers of mountain bikes and have a long history of creating very well-renowned knobby-tired bikes, their road bikes (including the legendary Hakkalugi) were beautiful, albeit rare, machines. My love of the Spanky led to hunting the elusive Hakkalugi, which is one of my favorite machines.

Metal bikes have had a revival recently, perhaps as MAMILs have gotten past their carbon fixation and have come to terms with the fact that there will be no last-minute call-ups to the Tour this (or any) year. Carbon frame design has evolved as bikes have taken some of the harshness out of the ride and added compliance in the form of seatstays slightly smaller than a pencil. Somehow, every year, they claim to be both stiffer and softer by double digit percentages over the previous model. Ride quality has improved over the bikes of the early 2000, and carbon is king rather than exotic. As snazzy as these frames look, however, they are still missing a quality a metal bike has: soul.

Metal bikes speak back to you- they call to you, sing to you, and tell you things. As I browsed teh interwebz one day, I saw the Enigma Ethos languishing on a forum classifieds post. Like the pictures of sad puppies and kitties begging for adoption, this bike had big sad eyes that told me how lonely it was. A display bike from NAHBS 2018, it had been taken around to see dealers but had never been ridden. The importer had posted the bike on the forum, and it had sat there for several months. As a SRAM nerd, I wasn’t really interested in its Shimano grouppo, and as a MAMIL, the 39/53 chainrings were certainly intended for thighs much younger than mine.

The dropouts had a graceful curve and integrated disc brake mounts, and the fork was painted to match the frame.It’s possible that the frame, handmade in England by Enigma out of Columbus Zona tubing, wasn’t fashionable, with quick-release dropouts, post-mount brakes, and 1-1/8″ non-tapered headtube, leading to the long months it spent on the forum, looking out at perspective buyers, tears welling in its eyes (or at least, rack eyelets). 2020-vintage bikes require these elements, and though I have them on other frames, I am not entirely convinced that riding a frame without them is a threat to my cycling experience.

If I recall correctly, we MAMILs rode quick releases and straight 1-1/8″ steerers with disc brakes on mountain bikes for about 20 years before thru-axles and tapered steerers became the norm. There were few QR-disc related injuries or fatalities. As this bike would stay on pavement, I could see no reason why it wouldn’t become another candidate to inhabit my basement.

Enigma started building steel and titanium bikes in 2006 and quickly gained a reputation for high quality, well-designed frames. They have won awards at NAHBS and other shows. Based out of Sussex, England, their team of craftsmen have won accolades for well-designed, high-quality bikes. Imported into the US by Velocipede Imports, the bikes are gaining a presence and are well received by the forum-dwelling experts of all things cycling. I had read several reviews of Enigma bikes, mostly on UK cycling sites, but was aware of their products and favorable (favourable?) write ups.

I contacted the seller, Michael, and he told me how the frame had been at NAHBS, and more of its history. I certainly had absolutely no need to bring another frame into the house, but within seconds of being told his price, I sent the money over. Like ripping off a bandage, paying for a bike should happen quickly, and without forethought as to if it was a good idea. Similarly, he wasted little time pulling the Shimano parts off and packing it up. I waited until my wife had gone to bed, then went downstairs and rearranged all the bikes so she would lose count.

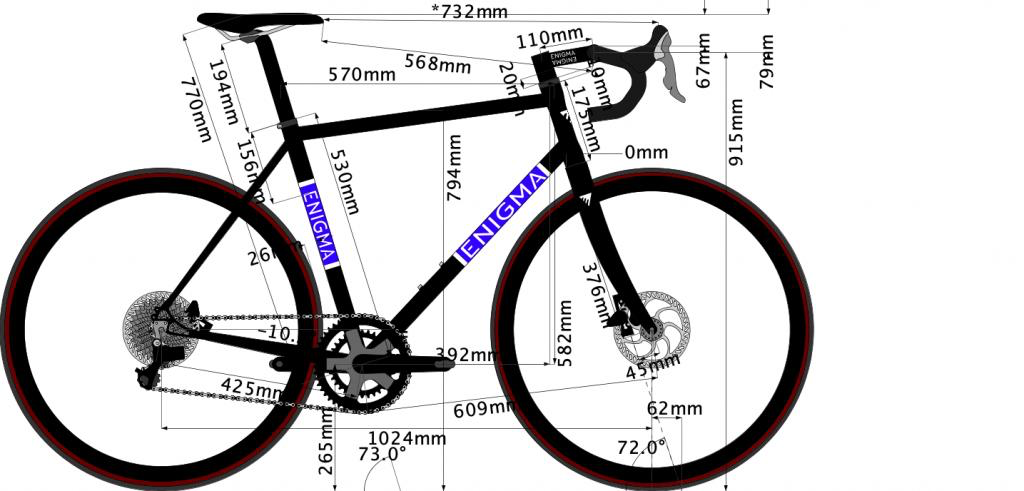

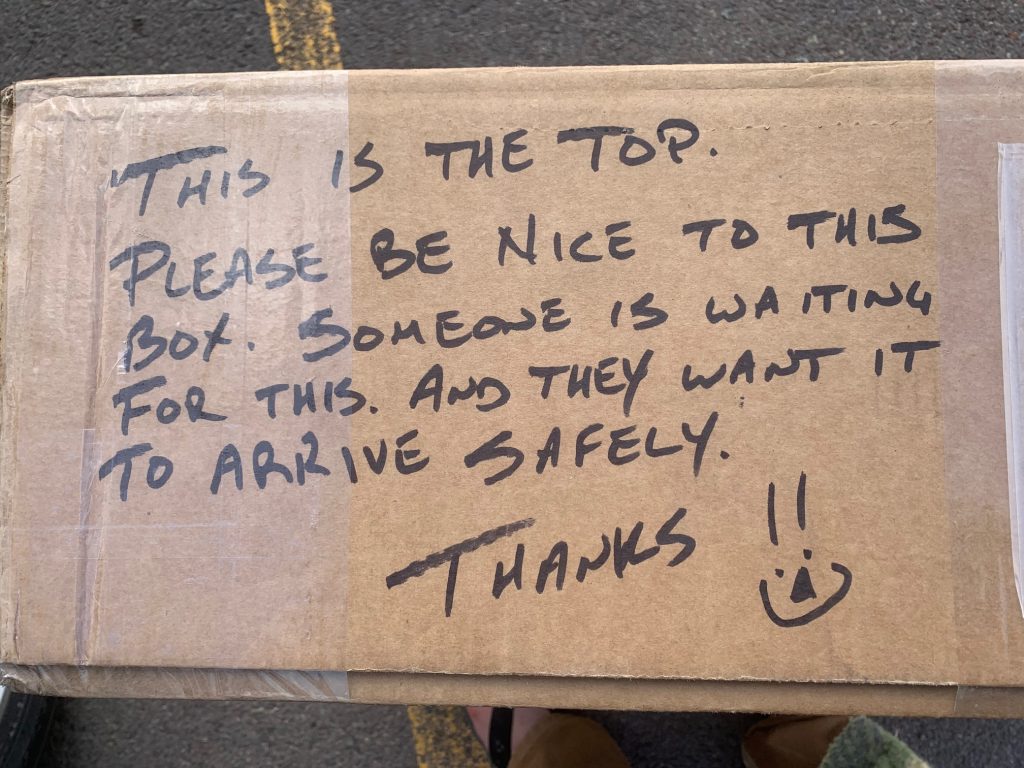

A few days later, it arrived at my house, packed like a fine piece of art. The box was well-labeled, including the bottom. Inside, the frame was wrapped, padded, and attached to a piece of cardboard that spanned the box.A smaller box inside, glued to the outer box, contained small plastic bags with all of the associated small parts: derailleur hanger, barrel adjusters, seatpost collar, headset, touch-up paint, and so forth. An Enigma-branded folio inside included a drawing of the frame with all geometry, an original build sheet, serial number documentation, and other specific information.

It took a few days of shifting grouppos around between framesets, swapping parts here and there, ordering a few, selling some, and scrounging others, but before long, the Enigma was built up with SRAM eTap with hydraulic brakes, a titanium layback seatpost, FSA Metron 4D bars, and a custom SLR saddle. I needed wheels, however, and was at a bit of a loss as to whether I should lace up a pair or buy a set.

The Enigma has a classic panel graphic, with a gloss black frame, metallic blue panels and white text. Matching paint details on the fork and downtube offer a subtle, elegant, and classic design as a skinny-tubed steel frameset should have. I used blue bar tape, which may be a stylistic risk as the blues are close, but not true matches. I will no doubt hear from the Style Police. While wanting to highlight the blue accents was a consideration for making the hubs all matchy-matchy, the budget considerations excluded basically everything in the Industry 9 AnoLab. I love the way those wheels look, and my own sets of I-9 hubs have been flawless performers, but for now, a wheelset is out of reach. While talking with Velocipede Imports about options, he suggested Hunt wheels, which he also imports.

After a bit of research, I settled on the Hunt Aero34, which is an unusual alloy-rimmed aero wheelset. It’s remarkably well priced, reasonably light, and is very modern in its width and tubelessness.I ordered them up, installed them, checked all requisite bolts for tightness, and headed out to see how this sleek black beauty rode.

If you’ve made it through all of the above 1600 words into this review, keep going. This is the part where I actually review the bike. Elsewhere on this site I note that I am prone to rambling; it’s a perk of old age.

A cold spring day met my first foray on the bike. In Colorado, we get huge amounts of snow in April, just as everyone is emerging from under piles of smelly ski gear in hopes of seeing their shadow and six more months of winter. If summer falls on a weekend, we usually have a picnic. We have short weather memories here: we forget that it snows in April as we want warm days, while November is typically dry as we eagerly wax our skis in anticipation of skiing. As is common this time of year, I headed westward into the afternoon breeze, which was strong enough to make my ride trend in a distinctly eastward direction.

I put my head into the wind and hands in the drops as I headed down-canyon, dodging flying concrete blocks and stray cattle blowing in the wind. Small trees bent in supplication as I rode by, and despite the headwind, I could feel how delightfully smooth the bike felt on the pavement. I had the Hunt wheels at 80PSI, which actually felt a bit firm, so on later rides I adjusted to a slightly more plush 75. On this first ride, though, I was very pleased with how the bike glided down the slightly descending road.

Once the warm-up descent (if coasting for 4 miles can be considered a warm-up) was over, I pointed the bike upward on one of my go-to climbs. The road tips up quickly, going from -3% to 17% in about 200 yards. The bike climbed well, despite the skinny, traditional tubeset (seattube of 28.6mm, 68mm BSA bottom bracket, 34.9mm downtube), and as I pedaled I felt no discernible flex in the bottom bracket. Like most steel bikes, it doesn’t have that leap-forward feel that carbon bikes with massive bottom brackets offer, instead providing consistent acceleration up to speed. In my case, a tiny amount of speed, but speed nonetheless.

As the pitch approached 10%, the bike fairly urged me to get out of the saddle, and once standing, it continued to climb extremely well. I’ve ridden this grade dozens of times on my Spanky, and that bike much prefers to have me seated. As the Enigma’s geometry is slightly slacker and significantly longer (mostly due to the chainstays being adapted for discs), and both bikes have very similar tubesets in the front triangle, I give credit to the large, ovalized chainstays for propelling the bike uphill. The vertically ovalized Zona stays are visible on a wide majority of modern steel frames, and they belie the idea that one must have a bottom bracket surrounded in cubic meters of carbon in order to be stiff enough to deliver power to the rear wheel.

Simply put: the bike climbs. Over several rides on local climbs, I found that I was spending more time out of the saddle, as well as climbing at least one cog taller than either my Spanky or my breakaway travel bike (titanium, with very large diameter tubes, and a plate chainstay: very stiff. All 3 bikes have identical gearing). On other steel bikes, what I thought was frame flex turned out to be bottom bracket spindle flex. Tossing the tapered spindle in favor of a modern 30mm spindle with outboard bearings makes a quiet bottom bracket, with no front derailleur rub, even if I put all of my beer-fueled pure MAMIL-mass into the pedal.

Some MAMILs, myself included, have a strong affinity with gravity, and as such, tend not to ascend steep hills at a measurable amount of speed. It has been suggested that I resemble a very lifelike statue, such is my impressive ability to climb at speeds that demonstrate my exceptional sense of balance. My climbing efforts are often mistaken for trackstands. On this bike, however, I show distinct signs of forward motion that even a casual observer may become aware of, if given a few minutes for proper study.

I compared that Strava segment with previous rides, and my times matched my fastest, set in 2011 and ’12, when I foolishly thought 39/53-11/26 was a good climbing setup. We’ll ignore the fact that nearly a decade ago, I still could see my feet without a mirror. It is entirely possible, that in those heady days of youthful exuberance, I could even touch them. As my hairline has receded along with my muscle mass, suddenly finding that I am riding at the same speed as my younger self, I can only conclude that it is really all about the bike, because I sure as hell am not the reason.

Over several weeks of riding the bike, its personality has begin to make itself known to me. The bike is smooth, with tubeless 28c tires at 75PSI, and it likes pavement. I’ve ridden some hard-packed road base, both with fresh grading and magnesium-chloride sealcoat, and some that are awaiting that treatment, and this bike is no fan of chunky, broken roads. It’s a road bike, not an all-road bike. It likes pavement, and who am I to argue? I have a gravel bike, and I’m not afraid to use it.

As a road bike, it excels. It’s quiet, smooth, and handles well. There are no surprises, no twitchiness on descents, no chatter or speed wobbles. It arcs well into corners, and responds to solid countersteering as if it was on rails. Over long hours in the saddle, it absorbs enough road chatter that you feel fresh at the end of the ride, other bikes I’ve ridden were much stiffer and fatiguing.

If I had to pick a negative, as a reviewer is somehow obligated to do, I suppose it would be the paint. Don’t get me wrong- it’s beautiful. Simple, classic, elegant, and with tiny details that only appear on the second look, this paint job explains why Enigma has won Best Paint awards. I have become accustomed to powder coated frames, and the powder is amazingly durable. The Enigma is wet-coated, and is showing some chipping and flaking at contact points (dropouts, bottle bosses, etc). Scratches and cable rub are a threat to the finish, something that is not an issue on my powdercoated bikes. It simply means I have to be careful, and live in a constant fear of the bike tipping over.

Overall, through, this bike is a work of art. This is part of the resurgence of metal bikes. It seems that after we’ve all tried something plastic, we’re looking for a bike that’s about more than weight, epoxy, aero shapes, and 10% stiffer than previous models. While on a ride with a fellow MAMIL who was astride his Breadwinner Lolo, our bikes spoke to the quality of what riding a steel bike is about: we rode for hours, chatting, stopping to see friends we encountered on route, climbing, descending, and whiling away the day in a fantastic combination of enjoying our machines, challenging our heart rates, and arguing over our recovery beer preferences. The Enigma crew created the perfect machine for exactly this purpose: to spend a long day in the saddle, enjoying the simple act of pedaling a bicycle.

3 Replies to “Steel Yourself: Enigma Ethos Disc”

Comments are closed.